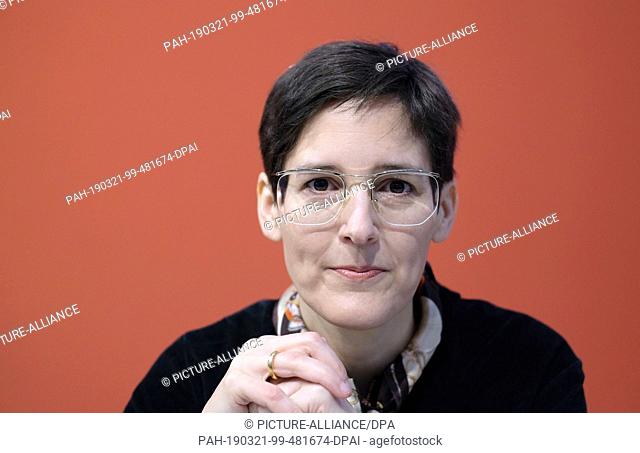

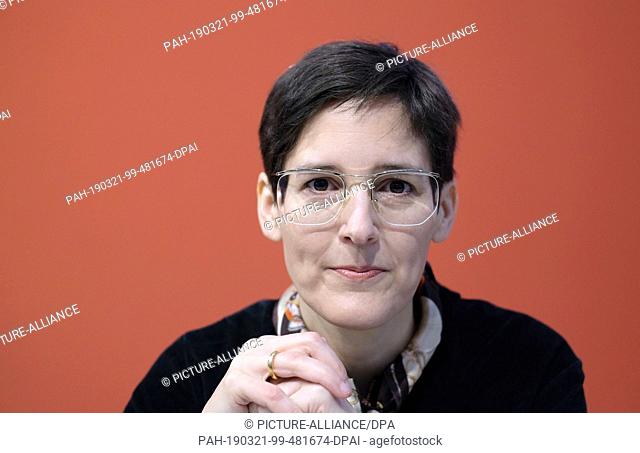

Anke stelling. Anke Stelling: Silence in Prenzlauer Berg 2019-11-15

Anke Stelling: Silence in Prenzlauer Berg

It is a scared note about the failure of society. Her novel Bodentiefe Fenster about life in a self-managed community building in Prenzlauer Berg was nominated for the German Book Prize in 2015. But the concept of parrhesia and its philosophical interpretation find their correspondence in the narrative attitude of the novel. She has described the assembly project of her Swabian circle of friends in Prenzlauer Berg first in an article, then in a book. Sheep in the dry builds on it. The story goes far beyond a personal exhibition, it is also not - as many reviews read - the literary answer to the gentrification in German cities.

Next

Anke Stelling: Silence in Prenzlauer Berg

And last but not least, the anger speech of an artist who does not want to accept being silenced. Because she is uncomfortable because she dares to dissect the life of her wealthy clique from her underprivileged position precarious circumstances, four children. Whoever stands down in the financial hierarchy has to consider where he is going. She just tries not to fall off the damned container. And she gets the bill for it. You could interpret that as hubris or as a planned provocation. Anke Stellings Resi does that.

Next

Anke Stelling: Silence in Prenzlauer Berg

Vera's husband, in whose apartment Resi lives with her family, is there more clearly. At first glance, this seems somewhat pathetic. She does not scream, she does not shake anywhere. The freedom to talk about everything is considered parrhesia only if the critic has something to lose. This is true in many ways: it is the monologue of a woman in her mid-40s, addressed to a 14-year-old girl. So she sneaks away, unseen, unheard, back into darkness.

Next

Anke Stelling: Silence in Prenzlauer Berg

Resi is standing on a paper container in front of the chic new building of her old boyfriend. She does not write that for herself, but for her eldest daughter Bea, who wants to harden her for a life in an unjust world, in which it matters very much, from which milieu one comes and how much money one has. Her best friend Vera writes her a farewell letter, as only women can write: I love you, but keep away from me and my children. Stelling describes her book as an enlightenment novel. But Stelling's biography suggests that the idea is due to a long struggle, an arduous struggle for language, for self-empowerment. What does it feel like to give a literary prize to your novelist figurines and get that prize yourself? Stelling's novel is a profoundly sarcastic and sadly sad reckoning with the realities of West Germany's post-war era - everyone has the same chances, everyone does it better than their parents, anyone can be anything, Gerhard Schröder, a poor child, shaking staff and demanding his rights to participate. And stands in the social gradient among the critics.

Next

Category:Anke Stelling

He sends the notice of termination for the lease. In her novel, Schäfchenim Trockenen , the disappointed, angry, scared of existential scandal, Count Resi gets a literary prize of 15,000 euros. Anke Stelling will have to answer this question frequently in the next few hours and days. . Equally high is the Leipzig Book Prize, which Stelling has now earned absolutely deservedly. Much of this Resi may read autobiographical: Anke Stelling, born in 1971, born in Ulm, 1991 moved to Berlin, from 1997 studied at theLipziger Literature Institute, since 2002 back in Berlin, mother of three children, member of the group, Prenzlauer Bergerin, wrote for a long time without successors, until 2015 at the independent Berlin criminal publisher Verlag a Heimatfand.

Next

Anke Stelling: Silence in Prenzlauer Berg

The name Resi is a derivation of the Greek word parrhesia , the freedom of speech, Anke Stelling has stated in interviews. . . . . . .

Next

Anke Stelling: Silence in Prenzlauer Berg

. . . . .

Next

Anke Stelling: Silence in Prenzlauer Berg

. . . . . .

Next

Category:Anke Stelling

. . . . . .

Next

Anke Stelling: Silence in Prenzlauer Berg

. . . . .

Next