Flannery o connor. Flannery O'Connor’s Stories “Revelation” Summary and Analysis 2020-02-04

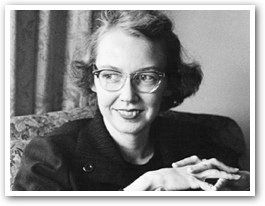

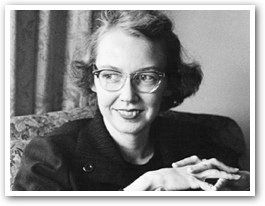

Flannery O'Connor (Author of A Good Man is Hard to Find and Other Stories)

Turpin's self-absorbed nature, since rather than feeling concern for the girl's health she is focused on how the girl's actions and attitude relate to her. As the trip goes on, the grandmother sends the family on a wild goose chase, seeking out physical proof of a misplaced memory. But the white-trash woman in the waiting room is also racist, and considers herself to be above black people. She was sitting on the sofa, feeding the baby his apricots out of a jar. Some critics have suggested that this chicken was early evidence of her later interest in the grotesque which is so much a part of her fiction.

Next

A Good Man is Hard to Find by Flannery O’Connor

In addition, it was the very house from which her maternal grandfather, Peter Cline, had served as mayor of Milledgeville for over twenty years. Turpin immediately starts a mindless conversation with the only other woman in the room whom she deems worthy, judging by appearance. She then enrolled in the Georgia State College for Women, later known as Georgia College, from which she graduated with a B. Who do you think you are? They seemed a much lighter blue than before, as if a door that had been tightly closed behind them was now open to admit light and air. Analysis Mary Grace's name marks her clearly as the symbol of grace in the story.

Next

Flannery O'Connor Biography

If the product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing! Turpin deliberately shows him kindness. GradeSaver, 12 July 2010 Web. Her essays were published in Mystery and Manners 1969 and her letters in The Habit of Being 1979. Turpin says that she and Claud own a home and land and have hogs which they keep in a pen so their feet don't get dirty; they keep them clean by hosing them down. While there she served as editor of the literary quarterly, The Corinthian, and as art editor for The Colonnade, the student newspaper. This dirt detour sends the family into a downward spiral that puts them face to face with what the grandmother hoped to avoid from the outset — the Misfit. Turpin's revelation at the end of the story, when she sees herself, Claud, and those of equal socioeconomic status bringing up the rear of the procession to Heaven.

Next

Flannery O'Connor (Author of A Good Man is Hard to Find and Other Stories)

She is like the hogs, below humans, because she is unable to see that all people are equal before God. Turpin considers to be pleasant, is the mother of an extremely unattractive, fat, teenage girl who is reading a book called Human Development and scowling. When she was five years old, a Pathé newsreel featured her and a pet Bantam chicken possessed of the ability to walk both backward and forward. It is here, for example, that one learns that Mrs. Turpin to sit because a dirty child is taking up too much space on the sofa.

Next

Flannery O'Connor Biography

There is nowhere for Mrs. In 1988 the Library of America published her Collected Works; she was the first postwar writer to be so honored. Instead, her mother talks about how ungrateful she is and what a shame it is that she has such a bad disposition. However you choose to read this story, as one of good old-fashioned murder, or a story of murder inextricably bound with issues of class, race and religion, you are left with comparable sense of dread, and maybe just a hint of schadenfreude as the grandmother finally gets her lips zipped. All of sudden, the girl seems to lose patience and slams her book shut to stare directly at Mrs. She tries to justify their existence in her mind, thinking about how smart they are and all that they can do. Though they are saved, they must follow those whom Mrs.

Next

Flannery O'Connor Biography

The vision reveals to her that all people are equal in God's eyes, and she is successfully moved. Mary Grace's eyes are particularly important as symbols of her judgment of Mrs. Turpin sprays down the hogs violently, as if trying to wash away her own sins by cleaning her animals. Turpin recognizes Mary Grace's closeness to God in that moment, and her desire for a revelation which she receives, though it is bizarre and not what she expected. They are alone on the road in a deserted part of the state where gas stations come only intermittently, setting a tone that leaves us unsure of our surroundings and insecure about the future. Turpin, as well as other humans, are like hogs in many ways. Aside from occasional lecture trips to colleges and universities, an occasional trip to visit friends, a trip to Lourdes and an audience with the Pope in 1958, and trips to Notre Dame in 1962 and to Smith College in 1963 to receive honorary Doctor of Letters degrees, O'Connor spent most of the remainder of her life in and around Milledgeville.

Next

A Good Man is Hard to Find by Flannery O’Connor

A long road trip Because of that, we as readers are extended participants in this very long road trip. This woman, who is dressed stylishly and whom Mrs. Before they have finished drinking, she goes back into the kitchen and decides to go to the pig parlor. Mary Flannery O'Connor, the only child of Edward Francis O'Connor and Regina Cline O'Connor, was born in Savannah, Georgia, on March 25, 1925. She believes the past was best, children should be quiet, women should always be ladies, and her opinion is always right. Because it has appeeared in many anthologies, this story is one of her best known, if not necessarily her best. There they took up residence in her mother's ancestral home, an antebellum brick house which had been constructed in the 1820s.

Next

Flannery O'Connor Biography

Contributed by Jillian McKeown; excerpted from on. Turpin a wart hog, and the comparison weighs heavily on Mrs Turpin's mind. Be that or not, it is evidence of her abiding passion for fowl, a passion later gratified by the multitude of ducks, geese, guineas, peafowl, and other assorted birds with which she was to populate her mother's dairy farm, Andalusia. Needless to say, as I finished the first story, which is also the namesake for my particular edition, I was completely taken aback. They spend the afternoon lying in bed resting, and while Claud sleeps, Mrs. Mary Grace continues to show signs of losing patience with the conversation as her mother, Mrs.

Next