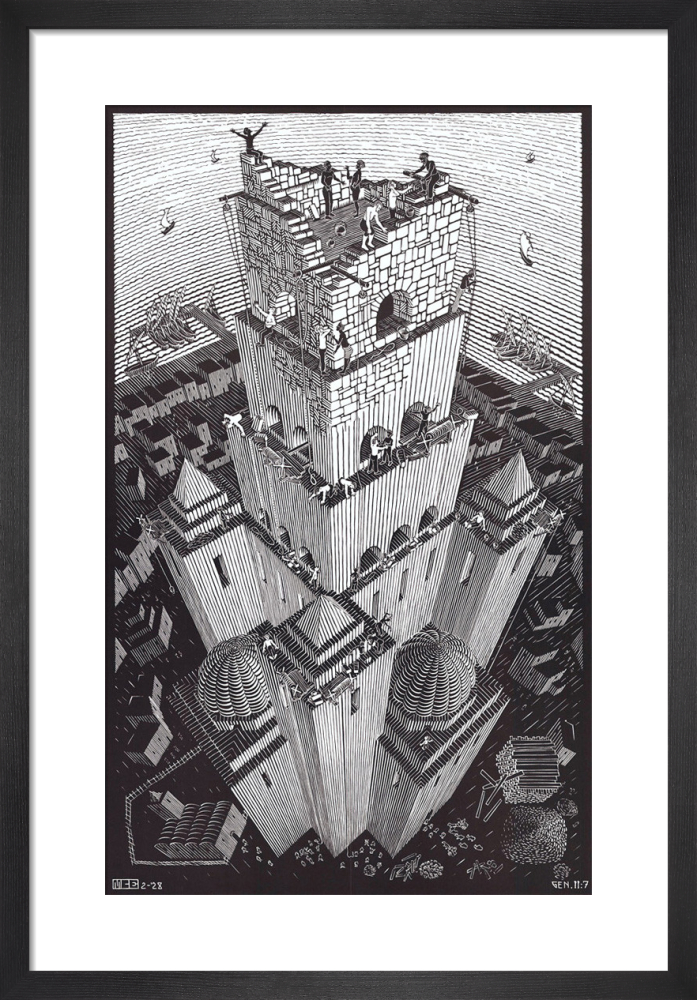

Mc escher. The Waterfall by M.C. Escher 2019-11-28

TOP 10 MOST FAMOUS AND BEST WORKS BY MC ESCHER

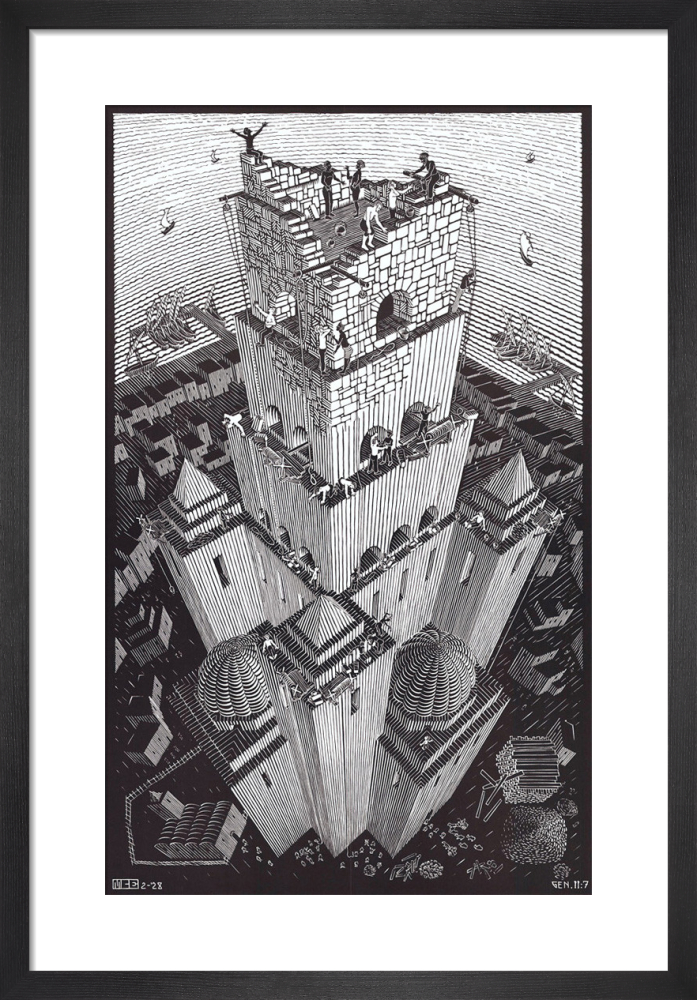

In one of his papers, Escher emphasized the importance of dimensionality: The flat shape irritates me—I feel like telling my objects, you are too fictitious, lying there next to each other static and frozen: do something, come off the paper and show me what you are capable of! Archived from on 17 November 2015. The exhibit features an extensive collection of drawings, mezzotints, lithographs, and woodcuts, which blend and blur constructs inspired by impossible worlds, the intricacies of nature, and the infinity of chess. In the same year, he traveled through Spain, visiting , , and. Starting in 1937, he created woodcuts based on the 17 groups. Escher: A mathematician in spite of himself. No major exhibition of Escher's work was held in Britain until 2015, when the ran one in from June to September 2015, moving in October 2015 to the , London. Additionally, some of his prints provide visual metaphors for abstract concepts particularly that of infinity, the depiction of which Escher became interested in later in his career.

Next

The impossible world of MC Escher

Examples of the former include Lizard 1942 and Regular Division of the Plane 1938 ; the latter, Sky and Water I 1938. The two-dimensional reptiles on a sheet of paper come alive and begin to creep over the desk in an endless circle. Despite not having a formal mathematical training, Escher had an intuitive and nuanced understanding of the discipline. The Museum obtained all of the documentation and the smaller portion of the art works. From 1919 to 1922, Escher attended the School of Architecture and Decorative Arts, learning drawing and the art of making. These feature impossible constructions, explorations of infinity, architecture and tessellations.

Next

The Mathematical Art of M.C. Escher

This drama is heightened by the overall darkness of the image and the strong contrast between these tones and the paler highlights. In 1922 Escher left the school, having gained experience in drawing and making woodcuts. The image encapsulates Escher's love of symmetry; of interlocking patterns; and, at the end of his life, of his approach to infinity. By continuing to use our sites and applications, you agree to our use of cookies. Roger Penrose sent sketches of both objects to Escher, and the cycle of invention was closed when Escher then created the machine of Waterfall and the endless march of the monk-figures of Ascending and Descending.

Next

M.C. Escher

The critic Steven Poole commented that It is a neat depiction of one of Escher's enduring fascinations: the contrast between the two-dimensional flatness of a sheet of paper and the illusion of three-dimensional volume that can be created with certain marks. It is likely that Escher turned the drawing block, as convenient, while holding it in his hand in the Alhambra. It is an honor to present M. Despite his massive fame in popular culture, Escher never fit into one style of art nor was he recognized as an important artist by the art community during most of his lifetime. Escher Company, while exhibitions of his artworks are managed separately by the M.

Next

The Waterfall by M.C. Escher

After graduating, Escher and a group of friends traveled to Italy and immediately fell in love with the culture and landscape, particularly the areas with steep slopes. He died in a hospital in on 27 March 1972, aged 73. See our for more information about cookies. Among his greatest admirers were mathematicians, who recognized in his work an extraordinary visualization of mathematical principles. The complexity of recognizing polyhedral scenes. Escher's painstaking study of the same Moorish tiling in the Alhambra, 1936, demonstrates his growing interest in tessellation.

Next

M. C. ESCHER

The sketches he made in the Alhambra formed a major source for his work from that time on. From 1919 to 1922, he studied at the School of Architecture and Decorative Arts in Haarlem, Netherlands, but lost interest and chose to pursue graphic arts. He had no interest in politics, finding it impossible to involve himself with any ideals other than the expressions of his own concepts through his own particular medium, but he was averse to fanaticism and hypocrisy. His works have similarly been used on many book covers, including some editions of 's Flatland, which used Three Spheres; 's Meditations on a Hobby Horse with Horseman; Pamela Hall's Heads You Lose with Plane Filling 1; Patrick A. In popular culture Main article: Escher's fame in popular culture grew when his work was featured by in his April 1966 in.

Next

M. C. Escher: Facts and Information

The heads of the red, green, and white reptiles meet at a vertex; the tails, legs, and sides of the animals interlock exactly. The Magic Mirror of M. Escher Foundation, and transferred into this entity virtually all of Escher's unique work as well as hundreds of his original prints. National Gallery of Art, Washington. This enigma is further enhanced by the fact that Escher gazes directly out of the picture instead of representing himself drawing the image. He was 70 before a retrospective exhibition was held.

Next

The Mathematical Art of M.C. Escher

His captivating illusionistic spaces, staircases that lead to nowhere, and his endless reflections are so recognizable though most viewing them do not realize the decades of studies he labored over to create these seemingly playful scenes. It was used as the basis for his 1943 lithograph. The family next moved to Château-d'Œx, Switzerland where they remained for two years. The care that Escher took in creating and printing this woodcut can be seen in a video recording. Inspired by Relativity, Penrose devised his , and his father, Lionel Penrose, devised an endless staircase. The townscapes and landscapes of these places feature prominently in his artworks. Chapter 5 is on Escher.

Next

Escher NYC

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/63572426/stair1.0.jpg)

He spent much of his time drawing and his artistic talent was recognized by an art teacher who began to teach him printmaking. Escher exhibitions organized by them are not supported by us, and they are not authorized by The M. The lithography print Reptiles combine the abstract mathematical with the vividness of nature. This image is not a painting, but a woodcut made by Escher himself. Therefore the strip has only one surface.

Next

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/63572426/stair1.0.jpg)